Rethinking Memory and Relationality

through Embodiment and Collapsed Time

Heirlooming:

How is the standard life-history approach to oral histories limited? What of the dialogic encounter is lost? What is created? In this art and oral history exhibition, I introduce a decolonial theory of memory and method for its discovery and understanding. Calling upon folks to tend to various modes of communication and to center senses and affect, I ask, “How can we slow and deepen the ways in which we come to know and understand? What is at risk if we fail to do so?”

Heirlooming — my theory-method — is a way that memory is made and shapes the ways we move through and understand the world; a process by which we understand our relationality and the dynamics of what enters our circulation; and a device we can use to do memory work that brings to the surface what might not arise if feeling, the body, relational pathways, and pluralized temporalities are not explored. As a framework to encapsulate the various forms communication can take, heirlooming trains us to be attuned to and literate in various forms of transmission. It helps us to understand that memory and meaning formation, recall, and recounting involve an affective and polymorphous network of elements that integrate into a being, and it invites us to employ a methodology of accessing those memories and meanings through engaging affective, sensorial, and embodied details.

My formation of heirlooming builds from various Indigenous epistemologies (specifically detailed in my written thesis) regarding conceptions of relationality, memory, time, breath, and the multi-location of memory; embodiment theory; sensory, erotics, and affect theory; Black, Chicanx, and queer feminist theory; quare theory; placial philosophies and epistemologies; critical disability studies; Dian Million’s felt theory; Maria Cotera’s notion of encuentro; Gail Baikie’s Indigenist and Decolonizing Memory Work Research Method and the Decolonizing Critical Reflection (DCR) approach; memory studies; physiology; psychology; and biology.

Breathing Paintings:

Heirlooming in Action

The images in the film below — what I currently call ‘breathing paintings’ — are viewfinders to observe and consider what is created during an encounter but unseen, untranscribed, yet most certainly archived in memory sites (the body, environment, relationships, objects, etc.) and meaning. As artistic renderings of affective and sensorial pathways and memory sites, these images are created by the sonic waves produced by audio recordings of oral history interviews I conducted. Using the body’s expressions as they were recorded when recounting memories as a medium, they demonstrate a form of notation for not just what a narrator says, but how they express memories, perspectives, and meaning. They are living portraits of the multi-sensory, multimodal transmission that is created during the remembering, the recounting, and the exchange — what is breathed to life when we remember, share, and witness. They are artifacts of the singular, unrepeatable fingerprints of an encounter that are illustrative of the constancy of the sensory in every moment, as well as the reverberations, impressions, growths, traces, and remnants made in and left on the witness and the storyteller.

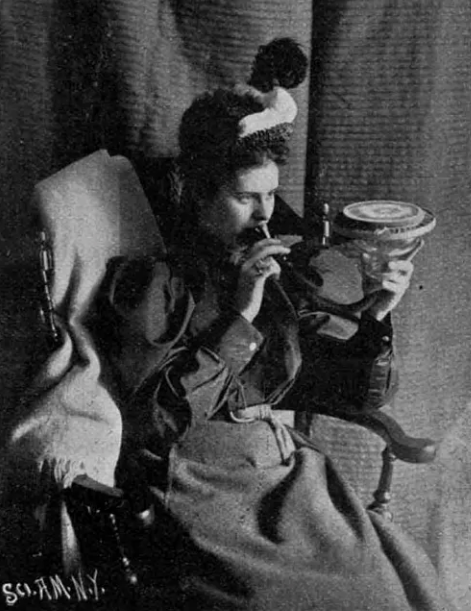

While developing the theory-method of heirlooming, I was inspired by cymatics — the study of sound wave and vibration phenomena and their visual representations — and Margaret Watts Hughes’ 19th-century Eidophone, a device she invented to measure the power of her voice while singing individual notes by watching seeds, pigments, and paste move over a rubber membrane. I set out to create a visceral, visual, and tactile transcription of the unique expression of stories each time they are recounted, gesturing to all that informs and is created by that distinctive, unrepeatable encounter. Iterating from Watts’ Hughes’ Eidophone, I took the notion of slow and deep listening to its extreme: using a clip of oral history interview audio, I looped each tone of a narrator’s spoken phrase and recorded the effect of its sound waves on paint and paste through a membrane. Because each story might have thousands of tones, I zeroed in on parts of the recordings wherein the narrator was expressing a significant memory and memory site in relation to their sense of self in order to demonstrate this notion and phenomenon. I placed a bluetooth speaker inside a vessel (the most effective by the first exhibition date was a plastic bucket), covered it with a plastic or rubber membrane, made the membrane taut with several rubber bands, and covered it with paints, wheatpastes, plaster of paris, and/or glycerine. Then, I played the looped tones through the speaker at its highest volume to form sound wave amplitudes large enough to make them visible to the naked eye. Sometimes I added more substances, played the audio until all the paints mixed into one color or spilled off of the edge, or ran it until the plaster dried, cracked, and jumped off of the device.

What’s happening here?

How were these breathing paintings created?

Image credit: scanned from Revista Blanca, Madrid, July 1, 1903

Image credit: scanned from Scientific American, May 29, 1897

Both images posted on https://medium.com/swlh/margaret-watts-hughes-and-the-shape-of-the-human-voice-d9f1a023c0c1

These images illustrate just one example of the many forms of communication that are not accounted for in standard life-history approaches to oral histories and archives. So much informs the shape, content, and feel of an encounter, both momentary and everlasting: The lifeworlds each interlocutor brings; the bodies they inhabit; the physical space(s) in which they come together; the environmental, social, geopolitical, financial, historical circumstances they find themselves in; the intersubjectivity their exchange creates; the questions asked; the answers offered and ways they are expressed; the postures; the gestures; the hesitations; the energies; the tensions; the silences. Here, we can think of this as how the membrane moves and the parameters it is constrained by; how the paints are chosen, fall, disperse, intermingle, and integrate; how the materials gain height, sculpt, undulate, and morph; and what traces are left behind. Though the tones spoken are those of the narrators, my actions in smearing the paste and dropping the paints are symbolic of intersubjectivity and the inability to remove the oral historian from the encounter and the product of it. Through these breathing paintings, I activate the archive and demonstrate heirlooming as a theory and method in action.

Many factors complicated the execution of this experiment, including access to materials and that no one in the past 140 years has managed to determine what paste Watts Hughes’ used to form her images. My process entailed much trial, error, and redesign of the device and its achievable products. A limited budget dictated what I could experiment with to build the device. Other materials I tested included unglazed and glazed ceramic pots, a metal stock pot, a plastic tray, and a glass vase. I tried various thicknesses of membranes, from plastic bags to rubber to latex sheeting. I used different sizes, shapes, and conduction styles (air and bone) of bluetooth speakers, whose sonic potentials varied greatly. I experimented indoors and outdoors, and in temperatures ranging from 36 to 88 degrees Fahrenheit. Each of these variables had a drastically different impact on the experiments. For example, at the higher temperatures, the plaster of paris set minutes faster than at cooler temperatures, which contracted the experiment: I had to mix and apply the substances to the membrane and initiate the sound waves much faster, before the substances hardened completely and disabled any movement. The rubber and latex membranes were too sensitive for the most successful vessel (the plastic bucket) and locking component (rubber bands) I had access to, and the heavy-duty garbage bags ended up being the best combination of reactive and stable that I could obtain at this juncture. Additionally, I discovered that the outcomes are drastically different when one speaks directly into the device as opposed to using a recording and speaker. Future trials will hopefully enable me to try using other construction materials and a higher-quality, isolated subwoofer.

Activating the Archive

with Affect and the Sensorium

The phrases painted here come from two interviews I conducted with narrators regarding their senses of self throughout their lives. With an interest in who and what seeps out when we think and speak of ourselves and what that reveals about our conceptions of time, I employed heirlooming to discover with narrators their memory sites, relationalities between them, and what memories and meanings reside in them.

In one clip, my father, Ron Seeley, is discussing the sound of loose change in his father’s 1950s suit pants pocket as he ran races with him in front of their home after returning from work. This is a memory and a site that holds my grandfather’s love for his children; the affective imprint the sound and attached act left on my father and his understanding of their relationship and my grandfather’s character; and my grandfather’s subjectivity from his difficult childhood and somewhat outsider social status, modes of expression, disregard for social norms, and endearing quirks.

“I remember the jingle, jingle, jingle, jingle, jingle…”

In the other clip, narrator Catlin Michael Wojtkowski shares a song lyric that speaks to his moral compass, politics, civic engagement, lived experience, and roots in the punk and hardcore music scenes.

“I’d rather die on my feet than live on my knees.’’

For a deeper dive into the theoretical and philosophical inspiration that seeded heirlooming’s creation and its connection to my practice and memory work at large, please explore my written thesis here.

This representation of “Heirlooming: Rethinking Memory and Relationality through Embodiment and Collapsed Time” is a digital version of a physical exhibition of the same name exhibited on Tuesday, April 29, 2025, at The Clemente Center, 107 Suffolk New York, NY.